Blurring the Lines Part III: Airpower Applications in the Gray Zone

Figure 1: The U-10 was a military variant of Helio Aircraft Company’s Super Courier. The Air Force, Army, and CIA used more than 100 aircraft in three different models during the Vietnam War. Here a U-10B of the 5th Special Operations Squadron is photographed over South Vietnam in 1969 (USAF photo)

The Gray Zone is characterized by intense political, economic, informational, and military competition more fervent in nature than normal steady-state diplomacy, yet short of conventional war. It is hardly new, however. The Cold War was a 45-year-long Gray Zone struggle in which the West succeeded in checking the spread of communism and ultimately witnessed the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

– Unconventional Warfare in the Gray Zone

Joint Force Quarterly (1st Quarter, Jan 2016)

First and foremost, one can see a trend of the disappearance of the line between states at peace and their shifting to a state of war… In addition, the make-up of participants in military conflicts is broadening. Together with regular forces, the internal protest potential of the population is being used, as are terrorist and extremist formations … There has been a shift from sequential and concentrated operations to continuous and dispersed operations conducted simultaneously in all spheres of confrontation and in remote theaters of military operations.

– Russian General Staff Chief Valery Gerasimov

Thoughts on Future Military Conflict—March 2018

Is the U.S. Air Force ready to fight in the “gray zone”?

After years of warfare in the Middle East, American security concerns are turning to Western Europe, where a resurgent Russia once again threatens the Atlantic alliance. This sea change is driving a reassessment of how the United States designs, deploys, and employs relevant forces for a great power conflict. The National Defense Strategy recognizes both Russia and China as peer competitors, but there is no reason to believe this portends a period of open, high-intensity warfare. Instead, it is much more likely that these competitors will continue to exploit “gray zone” conflicts to advance their interests at low cost and low risk. The recent history of Russian operations, from cyber attacks in Estonia to direct (although unacknowledged) employment of regular Russian forces among the vanguard of Ukrainian “separatists,” seems to promise more, not less, “gray zone” war – a conflict for which the Air Force is poorly equipped.

What is today called “gray zone” conflict has been well articulated by others, including the State Department, defense leaders, and think tanks. It is not new and has been called “political warfare,” “covert operations,” “guerilla warfare,” and “active measures.” But today’s Air Force has become hyper-optimized for low-intensity conflict scenarios that it is not likely to face in Europe. Its conventional footprint is too heavy to tread into austere basing or delicate situations, and existing special operations aviation capabilities are too small to provide the breadth and adaptability required for the range of grey zone operations – particularly the kind of deniable operations typical of Russian involvement in Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia.

This paper is the third in a three-part series called “Blurring the Lines,” which seeks to push the boundaries that have emerged to constrain airpower applications for a limited set of conditions. This installment explores new and partially new applications of airpower in the grey zone, focusing on logistics and communications. We note the potential of civil capabilities for military use and outline the airpower capabilities that the Air Force could use – if it had them – in this murky space between peace and all-out conflict.

Civil Aviation: A Closer Look

“Airpower” is often used as a euphemism for air-delivered firepower or the uniquely American capability to project conventional forces anywhere in the world. That definition describes the capabilities that the United States mostly holds in reserve for major combat operations but are less suited for gray zone operations.

In this article, we depart from the traditional focus on heavy, expensive airpower and examine “small-a” airpower in terms of one of its constituent parts: airlift intended to provide support for maneuver forces in the field. Rather than examining how many tons the Air Force can haul between continents, we are looking at its ability to deliver critical cargo over short distances, where and when it’s needed. As outlined in Part II of the series, the idea here is to expand the service’s aviation capabilities by matching civil aircraft and training with military needs. There is a vast market of airpower capability hiding in “plane” sight.

The United States has long found an application for civil aviation in the military sphere, observing from the high ground or moving goods and passengers. Etienne Oehmichen, a French engineer, flew the first quadcopter in November 1922, and, in the United States a month later, Ivan Jerome and George de Boze demonstrated the “flying octopus,” a quadrotor funded by the U.S. Army. While civil drones with cameras are commonplace today, hobbyists were flying cameras on remote controlled aircraft for decades before the first remote-controlled quadcopter. Civil aircraft carry cargo and passengers into otherwise inaccessible areas, and there is an entire “bush” aircraft industry dedicated to getting individuals and cargo into highly isolated locations. Today, all of this is done by individuals holding civil certifications, often years in advance of government interest.

Figure 2: The Ehang 184, a Chinese-built, pilotless, passenger-carrying electric octocopter during a demonstration flight (Ehang)

Gray Zone Airpower: Logistics

Airlift is an obvious application of airpower and one that civil aviation is particularly well-suited to fill. The ability to move single individuals, small groups, and equipment into disputed areas is an asymmetric advantage in Europe, which is festooned with roads, fields, and (in winter) frozen waterways. The universal presence of soccer fields provides ample space for bush aircraft. Larger flat surfaces might host short takeoff and landing cargo aircraft like the Twin Otter, long used in harsh and rugged conditions.

For completely runway-independent operations, the rapid proliferation of electric, vertical-lift civil drones has compelling potential. In Switzerland, a drone delivery service has made thousands of automated quadcopters to rapidly move highly perishable medical specimens. Policy changes and operations integration are the last remaining challenges for the United States and Europe, with more permissive nations such as the United Arab Emirates already seeing electric vertical takeoff and landing air taxis such as the Chinese Enhang 184 and German Volocopter. This evolution creates an opportunity for the U.S. military to benefit from evolutions in the civil aviation marketplace.

In gray zone conflict, small teams or even single individuals will be especially important. Dr. Phillip Karber, who has made extensive investigations into Russian operations in Ukraine, says Moscow’s most valuable weapon is the “agent in charge” who infiltrates targeted areas to develop intelligence networks and undermine local resistance. Just as the British Special Operations Executive made extensive use of Westland Lysanders to move operatives, the ability to insert counter-intelligence teams – or to extract agents – is a legitimate application of gray zone airpower.

Similarly, the responsive ability to deliver small payloads, particularly anti-tank or anti-aircraft teams, can have an outsize impact in a low-level conflict. Rapidly moving small teams, remote weapons, sensors, or critical supplies will be feasible in conditions where an adversary is themselves limited to imperfect situational awareness, and where the detection or destruction of a single tank can be the critical margin of success in a battle. Conversely, the Ukrainians discovered in Jun. 14, 2014 that the large, traditional airlifters present juicy targets.

Gray Zone Airpower: Communications & Intelligence

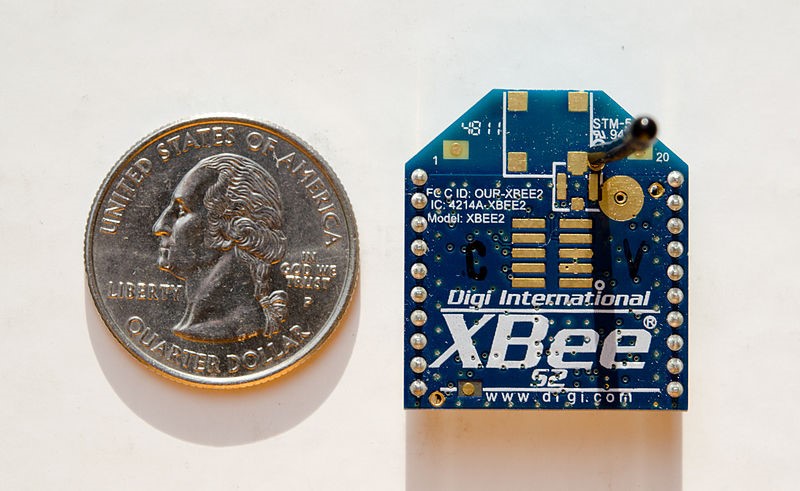

Another fruitful way to use civil airpower capabilities on future battlefields is to enhance or reinforce civil communications which might make it possible to maintain real-time communications, even without existing infrastructure. Civil designs provide an unremarkable (and unattributable) method of deploying capabilities into the field. Small telecommunications chips can be used to build a reliable, self-healing, encrypted network, making it possible to airdrop a telecommunications network made up of nodes the size of a candy bar. For instance, a single, low-level flight by a Cessna 172 could drop hundreds of nodes over a wide area, which could be used for maintaining situational awareness, sustaining counter-propaganda efforts, or other purposes. Moreover, a U.S.-controlled, air-emplaced communications network can serve as an entry point into public networks or networks controlled by hostile forces, enabling cyber teams to exploit otherwise closed communications.

Figure 3: An XBee wireless communications chip. Similar chips come in a variety of forms, can communicate over medium distances (40 km rural, 660m urban), and can run in a constant receive mode for more than a week on a pair of AA batteries (Photo by Mark Fickett under license)

Intelligence gathering using civil-derived assets is less about actually collecting intelligence with the aircraft and more about moving sensors (including small unmanned aerial vehicles) to the point of need. Using airpower to obtain accurate, timely information could help dispel much of the fog of war by undermining adversary efforts at disinformation. In conjunction with an air-inserted communications network, small, inexpensive sensors in the cell phone class might help detect and attribute hostile actions.

Systems like the Stingray cell phone tracker and its handheld variant, the KingFish, could be used to intercept and track cell phone usage. Not only might this provide real-time intelligence, it could also help “un-gray” the conflict, by identifying and tracking proxy forces who rely on smart phones for command and control – depriving those proxies the deniability that their state sponsor desires. Air insertion of phone trackers might be part and parcel of an inserted communications network. Small air-launched drones such as Perdix, intended for swarming applications, might well disaggregate to spread out sensor or communications coverage. Such a capability could help deny the Russians easy access to false storylines.

Indeed, much of the public unmasking of Russian activities in Ukraine has been a result of the intelligence produced and distributed by smartphones. The potential of open-source intelligence, derived from smartphones, to unmask Russian military activities is so substantial that in February, the Russian Duma backed a law to ban smartphones and social media use by their military.

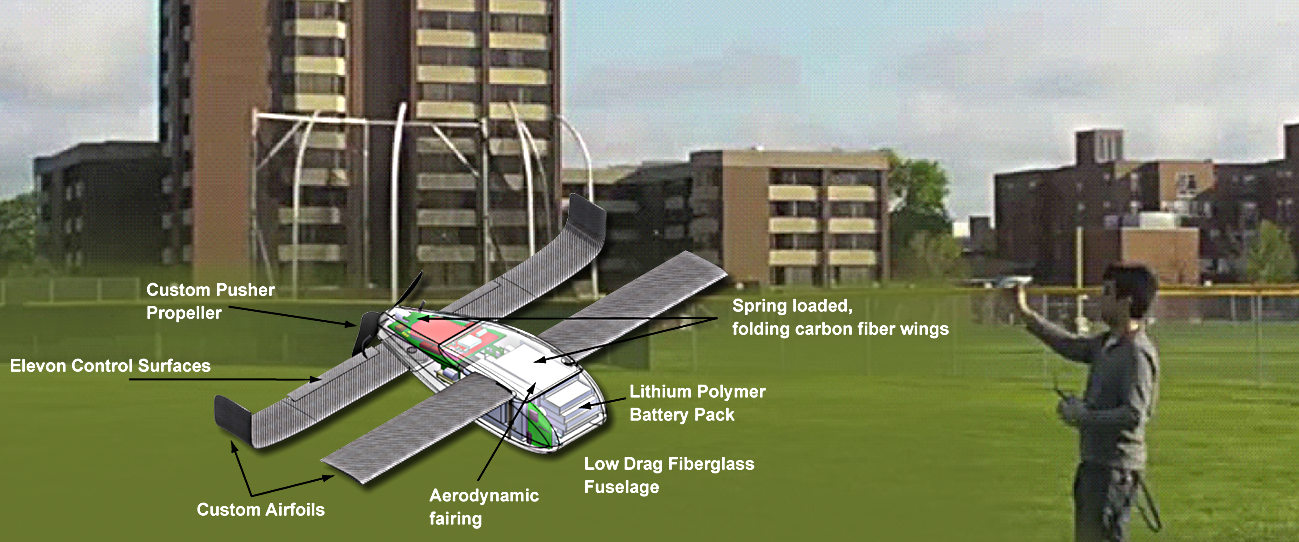

Figure 4: MIT’s Perdix micro-drone is essentially a flying battery with folding wings. Often touted as a swarming system, a de-aggregated cloud of Perdix might instead act as self-emplacing sensors or communications nodes (MIT)

The Right Stuff: Providing the Force

Though the military has long made use of civil airpower, today’s conventional Air Force is almost exclusively equipped with military-specific designs that have little linkage to civil designs. This is a missed opportunity – there is no shortage of useful civil aircraft.

The airpower capabilities we envision are intended to be part of a forward Air Expeditionary Task Force, not part of the global mobility enterprise managed by Transportation Command. Essentially, they are aligned to air divisions to provide intra-theater mobility in the exact same way that CH-47s or MV-22s (also not managed by Transportation Command) provide Army and Marine maneuver forces organic airlift. With much of the Air Force’s heavy airlift dedicated to supplying the Joint Force, light “tactical” airlift could occupy an unfilled niche, servicing forces in the field rather than large, easily targeted airbases.

The United States could soon face a similar challenge in Europe as it did in Vietnam. In that conflict, the twin engine C-7 Caribou, the high-wing U-10 Super Courier, the L-4 Grasshopper, and U-7 Super Cub, or the U-21 Ute, were all civil designs that provided critical military tactical mobility. Our vision heavily emphasizes short and vertical takeoff aircraft to help operate from unimproved or damaged airstrips. The largest vehicle would be a twin turbo-prop transport like the Viking Air Twin Otter 400, a modernized, in-production transport that the U.S. Army uses for the Golden Knights parachute team. The Air Force also might employ genuine bush aircraft, many of them clones of the P-18 Super Cub, used for similar purposes in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. Crop dusters like the Air Tractor 802F or Thrush 710 could be used to haul liquid cargo, particularly fuel. Small civil drones could be used to emplace sensors or communication nodes, and the emerging electric vertical takeoff and landing air taxis offer useful cargo loads for short-hop, rapid-turn operations.

To provide pilots for the civil aircraft, we could turn to civil training methods (outlined in Part II of this series). The cost of producing an Air Force pilot today ranges from $600,000 to $2,600,000 depending on the type of aircraft flown, with fighters being the most expensive. On the other hand, the cost of training to become the pilot of a regional airline jet – similar to a Twin Otter – is more like $70,000, and takes much less time.

Figure 5: Ski-equipped Royal Canadian Air Force CC-138 Twin Otter (RCAF)

Transition to Overt Combat Operations

The use of civil airpower capabilities doesn’t end when open hostility starts – what was useful in the gray zone continues to have utility if the conflict escalates. With U.S. European Command and U.S. Indo-Pacific Command considering distributed combat operations – in which forces operate in small, rapidly shifting groups – light aviation will become an extremely useful tool. The Twin Otter, for example, can deliver around 3,500 pounds of cargo over operationally relevant distances, allowing it to support “clusters” of frontier bases or other field locations with personnel, tools, equipment, and munitions. One Twin Otter sortie could fully rearm an F-22; with eight air-to-air missiles, 480 rounds of ammunition, plus chaff and flares. A Super Cub clone could deliver 100 ready-to-eat meals and 324 full 30-round magazines of NATO 5.56 ammunition; enough basic supplies to sustain a full platoon or forward airbase team for days. Any number of emerging delivery drones could provide critical spare parts or repair damaged portions of a meshed communications network. A converted crop duster could carry enough jet fuel to refuel a Twin Otter – twice.

All of the capabilities used for gray zone warfare could also support distributed combat operations in an anti-access/area denial environment, with rapid resupply enabling fast-moving distributed operations to avoid adversarial long-range fire. Like all aircraft, these aircraft would be vulnerable to air defense systems, which could drive them to fly at extremely low levels. Europe’s high infrastructure density, rolling terrain, and relatively abundant tree cover makes low-altitude point-to-point flight viable; even under the engagement envelopes of Russian medium-range tactical surface-to-air missiles.

Even advanced heat-seeking, shoulder-launched weapons will be challenged to find low, slow, prop-driven aircraft, which present little in the way of friction-heated surfaces or jet exhaust plumes. Aircraft powered by internal combustion or electric motors present signatures that are almost completely outside the design of Russian and Chinese infrared seekers. None of this is to say that low, slow, turbo-prop or rotor designs are inherently superior, and the very real threat of engagement by anti-aircraft artillery or small arms should not be overlooked. But the civil designs tend to be slower, cooler (in the thermal portion of the spectrum) and smaller than their military counterparts, placing them in a target class that air defense systems are not optimized against.

The geography of Europe offers opportunities to utilize airpower across the continent in a fashion that the Russians cannot replicate. In 2014, Europe (including Ukraine) had 2,401 paved and 1,732 unpaved legal airports, plus an undetermined number of disused or uncertified fields. European terrain is extremely favorable to aircraft that can operate from unprepared surfaces, waterways, or roads, with well-mapped obstacles and short distances to divert should a particular airfield be unavailable. Employed as mobility, logistics, and communications enablers, civil aircraft can allow conventional air forces to maneuver in ways the Russians cannot target. While the Pacific theater lacks similar terrain, it shares with the European theater the need for operational-level maneuvers to disperse and survive.

In the 1920s, the United States experienced an explosion of general aviation capabilities which were used for both military and civil purposes. The Department of War (later the Defense Department) routinely repurposed civil designs well into the Vietnam era, but this has tapered off since. Today, only special operations forces make significant use of adapted civil aviation capabilities, leaving an opportunity wide open for conventional forces: The United States has an opportunity to use low-cost, widely available civil aviation capabilities to augment its ability to fight in the gray zone, or to disperse and maneuver in a high-intensity European conflict. The Air Force should take advantage of these conditions, returning to Europe some significant airpower advantage that is not reliant on expensive capabilities.

Col. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha was an instructor electronic warfare officer in the F-4G Wild Weasel and the F-15E Strike Eagle, amassing 156 combat missions over 10 combat deployments. As an irregular warfare operations officer, Colonel Pietrucha has two additional combat deployments in the company of U.S. Army infantry, combat engineer, and military police units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is currently assigned to Air Combat Command.

Lt. Col. Jeremy “Maestro” Renken is an instructor pilot and former squadron commander in the F-15E Strike Eagle, credited with over 200 combat missions in five combat deployments. He is a graduate of the USAF Weapons Instructor Course and is currently an Air Force Fellow assigned to Air Combat Command.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. Government.